Initial Evaluation of Use of NAT in Assignment of CMV and EBV Infection Status in Children Awaiting Solid Organ Transplant.

C. Burton, Y. Tong, J. Preiksaitis.

Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

Meeting: 2016 American Transplant Congress

Abstract number: C275

Keywords: Cytomeglovirus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Pediatric, Screening

Session Information

Session Name: Poster Session C: Viruses and SOT

Session Type: Poster Session

Date: Monday, June 13, 2016

Session Time: 6:00pm-7:00pm

Presentation Time: 6:00pm-7:00pm

Presentation Time: 6:00pm-7:00pm

Location: Halls C&D

Purpose: The presence of passive antibodies, transfusion-acquired or maternal in infants, can make serologic determination of pre-transplant CMV and EBV status in children unreliable. We evaluated nucleic acid testing (NAT) of throat, saliva, blood and urine samples as an adjunct to serology in assignment of CMV and EBV infection status in children awaiting solid organ transplant (SOT).

Methods: We enrolled 18 children, ≤18 yrs, awaiting SOT at our institution from July 2014-Nov 2015 and collected a throat swab, urine, saliva and blood sample on each patient. Demographic and clinical information including age, organ being transplanted, and transfusion history was collected. CMV NAT was performed on all samples using our in-house developed real time PCR assay. EBV NAT was performed on all samples except urine, using EBV Taqman QPCR. EBV and CMV serology was also performed. Subjects were considered to have potential passive antibody if they were <18 mos or had received blood products in 2 mos. prior to sample collection.

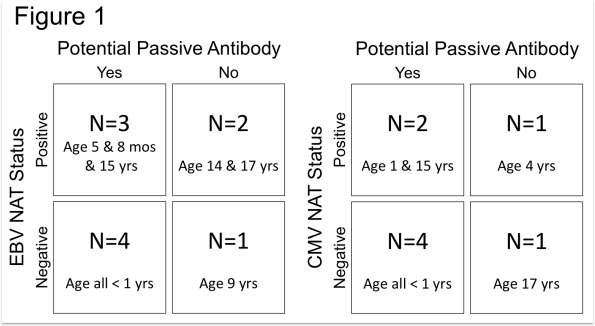

Results: We enrolled 18 children, age 3 wks-17.4 yrs (median 1 yr, IQR 0.4- 14.7) awaiting liver (8), heart (5), renal (3) or lung (2) transplant. Of the 8 CMV seropositive children, 3 were shedding CMV from urine and saliva (ages 1, 4,15 yrs.); 1/3 was also positive from throat swab and whole blood. Of the 10 EBV seropositive children, 5 were shedding EBV in saliva (ages 0.4-17.4 yrs.); 3/5 were also positive in throat swab and 2/5 had EBV detected in whole blood. Figure 1 outlines CMV and EBV shedding in seropositive children with and without potential passive antibody. The 10 CMV and 6 EBV seronegative children had negative CMV and EBV NAT respectively. One 4 mos. old, with recent transfusion, had indeterminate EBV serology and negative EBV NAT. EBV serology was missing in 1 child.

Conclusions: Our preliminary data suggest that addition of CMV (urine and saliva) and EBV (saliva) NAT testing may help identify true CMV and EBV infection in children in whom serology may be unreliable, including older children who have had received blood products. The significance of a negative CMV or EBV NAT in seropositive children requires further investigation.

CITATION INFORMATION: Burton C, Tong Y, Preiksaitis J. Initial Evaluation of Use of NAT in Assignment of CMV and EBV Infection Status in Children Awaiting Solid Organ Transplant. Am J Transplant. 2016;16 (suppl 3).

To cite this abstract in AMA style:

Burton C, Tong Y, Preiksaitis J. Initial Evaluation of Use of NAT in Assignment of CMV and EBV Infection Status in Children Awaiting Solid Organ Transplant. [abstract]. Am J Transplant. 2016; 16 (suppl 3). https://atcmeetingabstracts.com/abstract/initial-evaluation-of-use-of-nat-in-assignment-of-cmv-and-ebv-infection-status-in-children-awaiting-solid-organ-transplant/. Accessed March 1, 2026.« Back to 2016 American Transplant Congress